In what follows, we first provide details of the empirical methodology underlying our SWB approach, followed by a detailed discussion of the data with some summary statistics.

3.1 Empirical methodology

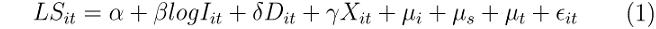

To apply the life satisfaction approach, we consider the following fixed effect model to estimate the impact of experiencing house property damage from a natural disaster on SWB for an individual:

where LSit is level of life satisfaction of individual i in year t and Iit is individual i’s annual household income. The natural logarithm of household income (log I) enters the regression equation to account for declining marginal utility of income.

Dit indicates whether individual i experienced home damage from natural disasters in year t. Xit is a vector of variables controlling for personal characteristics, such as age, household size, education level, health status, employment status, marital status, number of children, living areas (urban or rural), and health-related behaviour. μi denotes the unobservable time-invariant individual factor. μs and μt are state and year fixed effects, which are dummy variables respectively representing the state the individual resides in and the year of the interview. εit denotes the unobservable disturbance term.

Wellbeing regressions like equation (1) have been commonly used as a valuation tool for non-market goods. The estimated coefficients that link life satisfaction, income and natural disaster experience allow one to calculate the monetary equivalent of the utility loss from experiencing a natural disaster. Specifically, we use the estimated coefficient on log household income (β) together with the coefficient on the damage from disaster (δ). That is, the total cost of a natural disaster is the amount of log income required to compensate an individual to reach the same level of life satisfaction if they were to experience the natural disaster. In other words, we estimate the monetary transfer an individual (who has experienced natural disaster) would need to receive to return to their life satisfaction level before the event, otherwise known as the ‘compensating variation’.

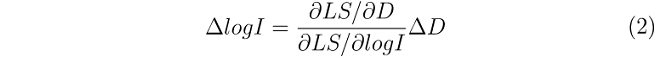

If life satisfaction (LS) depends on the income (I) and disaster damage (D), holding everything else constant, then the amount of log income required to compensate for disaster damage (∆LS=0), will be:

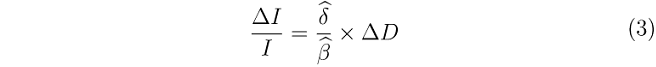

Based on regression results from (1), we can calculate the amount of income compensated as:

Intuitively, the severity of damage inflicted by natural disasters will require differing amounts of compensation for different individuals and households. As such, the accuracy of our costing will be highly dependent on the detail of damage experience available in the dataset. Unfortunately, data from the survey used can only indicate whether respondents have or have not suffered damage – a constraint that threatens to severely limit the ability of our approach to estimate the utility loss associated with different extents of damage. To partially overcome this, we make some assumptions on the probability that an individual will suffer from home damage from a natural disaster. For example, we could assume that the potential risk for disaster damage is reduced due to preventative measures (∆D) by a percentage ranging from 0 to 100.

3.2 Data

In this study, we use a population-representative longitudinal dataset, the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) survey. The HILDA survey is an annual household-based survey which collects a comprehensive set of panel information on people’s socioeconomic characteristics, wellbeing and family circumstances. The survey tracks more than 17,000 Australians each year, starting from 2001 when the survey was first conducted. Information collected includes responses to questions about experiences from any type of weather-related natural disaster in the past 12 months, which allows us to estimate the year-to-year effect of natural disasters. Information related to weather-related disaster events, such as floods, bushfires and cyclones, is available from wave 9 in 2009 onwards. This gives us 11 waves of HILDA data from 2009 to 2019 that we can use in our analysis. From here, we built a balanced dataset across 11 years, covering 41,962 observations from 13,085 households across eight states and territories.

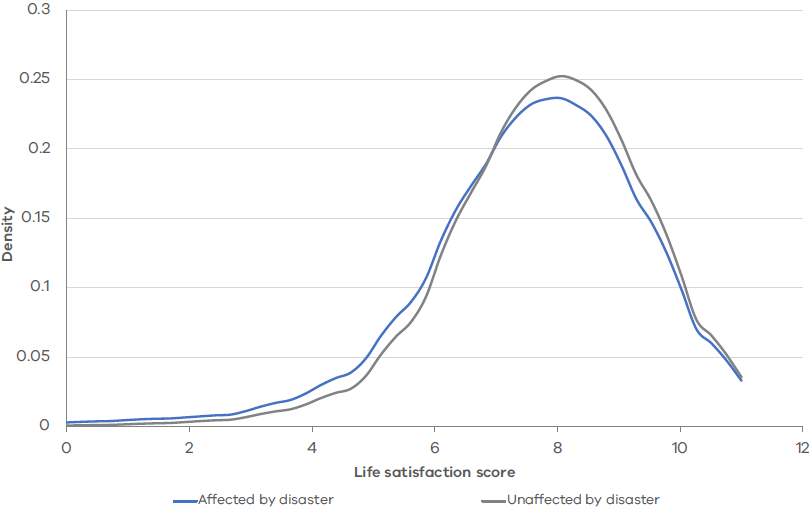

The dependent variable, respondents’ self-reported life satisfaction, is the categorical response to the following question: how satisfied are you with your life? The respondent chooses a number on a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means completely dissatisfied and 10 means completely satisfied. Figure 1 shows the density functions of life satisfaction for different cohorts. A visual inspection suggests that the cohort affected by natural disasters has a slightly lower average life satisfaction score than the cohort not affected.

Figure 1: Distribution of life satisfaction scores

To calculate the compensating variation, information on the two explanatory variables is extracted. The first variable, disaster experience, is obtained from the question: has a weather-related disaster (e.g. flood, bushfire, cyclone) damaged your house? The responses are further separated by gender and home ownership status in our analysis. For the second variable, income, we use respondents’ annual household income, defined as the sum of all household members’ gross income for each financial year.

Table 1 compares the means for life satisfaction score and main control variables for the different cohorts:

(i) between people who have experienced damage from natural disasters and those who have not

(ii) between homeowners and non-homeowners.

For cohorts grouped by experience, individuals who have experienced natural disasters, on average, have lower satisfaction, income and education. They are also more likely to be unemployed and to suffer from longer term health problems. For cohorts grouped by home ownership status, the summary statistics show homeowners feel more satisfied with their lives and have higher levels of income and education. Furthermore, homeowners appear to be healthier in the long term, with responses that indicate they smoke less and consume less alcohol than their counterparts who rent or board.

Table 1: Descriptive statistics for different cohorts

| VARIABLE | DISASTER EXPERIENCE | HOME OWNERSHIP | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOTAL | YES (M0) | NO (M1) | DIFF(a) | YES (M0) | NO (M1) | DIFF | |||

| Life satisfaction(b) | 7.849 | 7.615 | 7.853 | 0.238 | *** | 7.944 | 7.521 | -0.423 | *** |

| Household income ($1 000) | 133.105 | 122.966 | 133.262 | 10.296 | ** | 144.929 | 92.005 | -52.924 | *** |

| Household size | 2.858 | 2.793 | 2.859 | 0.067 | 2.951 | 2.535 | -0.417 | *** | |

| Age | 50.228 | 50.686 | 50.221 | -0.465 | 51.508 | 45.780 | -5.727 | *** | |

| Tertiary education+ | 0.311 | 0.262 | 0.312 | 0.050 | *** | 0.333 | 0.235 | -0.098 | *** |

| Long-term health problem(c) + | 0.213 | 0.268 | 0.212 | -0.056 | *** | 0.198 | 0.266 | 0.068 | *** |

| Employed+ | 0.886 | 0.839 | 0.886 | 0.047 | *** | 0.915 | 0.787 | -0.128 | *** |

| No. of children | 1.958 | 2.147 | 1.955 | -0.192 | *** | 2.012 | 1.803 | -0.198 | *** |

| Married+ | 0.624 | 0.604 | 0.624 | 0.021 | 0.705 | 0.344 | -0.361 | *** | |

| Living in urban area+ | 0.886 | 0.796 | 0.887 | 0.092 | *** | 0.891 | 0.867 | -0.025 | *** |

| Smoking++ | 1.681 | 1.768 | 1.680 | -0.088 | *** | 1.610 | 1.928 | 0.318 | *** |

| Drinking alcohol+++ | 5.337 | 5.315 | 5.337 | 0.022 | 5.325 | 5.377 | 0.052 | ** | |

Notes:

(a) Difference between the mean value in two groups.

(b) Life satisfaction scores are self-rated, with scores ranging from 0 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied).

(c) Self-reported binary response – with or without long-term health problems.

*** is significant at 1% level, ** at 5% level, and * at 10% level.

+ Binary; Base variables are without Bachelors degree, no long-term health problem, unemployed, single, rural.

++ Self-reported level ranges from 1 (never smoked) to 5 (smoke daily).

+++ Self-reported level ranges from 1 (never drunk alcohol) to 8 (drink alcohol everyday).

Table 2 reports the descriptive statistics across the waves. The sample means of the variables remain stable across the 11 years of data. Life satisfaction marginally increased over time, while the probability of experiencing a natural disaster fluctuated between 2009 and 2019, with a sharp decline in 2014. Average annual household income steadily increased by around 4 per cent a year while household size remained steady. It appears there was a steady increase in the number of people each year who obtained higher levels of educational qualifications, but employment rates in this sample cohort remained the same. It further appears that there was stronger preference for having children over the period, but fewer people were married, fewer were smoking and fewer were drinking alcohol.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics across waves

| VARIABLE | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life satisfaction(a) | 7.816 | 7.754 | 7.833 | 7.809 | 7.802 | 7.814 | 7.817 | 7.833 | 7.806 | 7.832 | 7.870 |

| Disaster experience | 0.014 | 0.016 | 0.033 | 0.015 | 0.015 | 0.007 | 0.017 | 0.012 | 0.014 | 0.013 | 0.011 |

| Homeowner+ | 0.766 | 0.765 | 0.786 | 0.770 | 0.766 | 0.770 | 0.795 | 0.777 | 0.777 | 0.780 | 0.795 |

| Household income ($1 000) | 116.794 | 118.932 | 128.675 | 132.692 | 137.891 | 141.227 | 147.295 | 148.168 | 151.750 | 158.649 | 164.190 |

| Household size | 3.032 | 2.998 | 2.984 | 2.973 | 2.966 | 2.950 | 2.930 | 2.924 | 2.905 | 2.912 | 2.879 |

| Age | 45.832 | 46.165 | 47.002 | 47.314 | 47.862 | 48.506 | 48.976 | 49.631 | 50.332 | 50.913 | 51.399 |

| Tertiary education+ | 0.305 | 0.309 | 0.333 | 0.315 | 0.318 | 0.329 | 0.345 | 0.328 | 0.337 | 0.339 | 0.350 |

| Long-term health problem(b) + | 0.173 | 0.179 | 0.166 | 0.180 | 0.188 | 0.188 | 0.178 | 0.188 | 0.180 | 0.190 | 0.182 |

| Employed+ | 0.883 | 0.885 | 0.910 | 0.885 | 0.877 | 0.882 | 0.912 | 0.875 | 0.898 | 0.890 | 0.907 |

| No. of children | 1.870 | 1.878 | 1.881 | 1.910 | 1.916 | 1.936 | 1.899 | 1.959 | 1.983 | 1.996 | 1.928 |

| Married+ | 0.634 | 0.631 | 0.639 | 0.628 | 0.627 | 0.624 | 0.635 | 0.622 | 0.623 | 0.626 | 0.629 |

| Living in urban area+ | 0.877 | 0.886 | 0.890 | 0.886 | 0.887 | 0.887 | 0.896 | 0.888 | 0.886 | 0.886 | 0.890 |

| Smoking++ | 1.726 | 1.723 | 1.700 | 1.694 | 1.679 | 1.691 | 1.663 | 1.666 | 1.659 | 1.653 | 1.634 |

| Drinking alcohol+++ | 5.457 | 5.402 | 5.420 | 5.432 | 5.404 | 5.397 | 5.414 | 5.360 | 5.374 | 5.326 | 5.359 |

Notes:

(a) Life satisfaction scores are self-rated, with scores ranging from 0 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied).

(b) Self-reported binary response – with or without long-term health problems.

+ Binary; Base variables are no disaster experience, non-homeowner, without Bachelors degree, no long-term health problem, unemployed, single, rural.

++ Self-reported level ranges from 1 (never smoked) to 5 (smoke daily).

+++ Self-reported level ranges from 1 (never drunk alcohol) to 8 (drink alcohol everyday).

Updated