- Published by:

- Department of Treasury and Finance

- Date:

- 1 Sept 2024

Tom van Buuren, Department of Treasury and Finance

Author contact details: veb@dtf.vic.gov.au.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Victorian Department of Treasury and Finance.

Suggested Citation: Tom van Buuren (2024), Unveiling household consumption dynamics: Analysing trends in GST revenue. Victoria’s Economic Bulletin, September 2024, vol 8, no 3. DTF.

Abstract

This paper introduces a data-driven methodology for estimating the goods and services tax (GST) revenue raised through household final consumption expenditure. The methodology centres around the use of input-output tables to derive the percentage of total household consumption subject to GST by broad consumption groups and in aggregate. In applying the methodology, it is found that between July 2000 (when GST was first introduced) and June 2019, the Australian household sector has consumed a greater share of goods and services subject to GST compared to consumption of GST-free items.

The study captures the immediate shift in household consumption since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, away from spending on tourism, hospitality, and in-person recreational activities which are all subject to GST. This is consistent with sudden border restrictions and necessary public health measures put in place throughout 2019‑20 and 2020-21. The study further demonstrates that a wave of discretionary spending followed the gradual easing of restrictions, leading to a notable and rare increase in the proportion of GST-chargeable goods and services within the household sector since the GST was introduced.

Using more recent data, the study shows that real household consumption on goods and discretionary items has since slowed down, contributing to a marked reduction in household consumption subject to GST. This downward trend is expected to continue as households moderate spending on discretionary items amidst cost-of-living pressures.

1. Introduction

The objective of this paper is to introduce a data driven methodology for tracking the total value and relative magnitude of the goods and services tax (GST) revenue raised through household consumption.

The methodology combines annual household consumption and GST data, then breaks it down into quarterly estimates of GST revenue raised from household consumption. This enables the monitoring of household consumption patterns and their impact on GST revenue. The methodology is achieved by estimating the per cent of household consumption subject to GST (‘percentage GST-able’) by individual categories (i.e. health or transport). This can provide insights into which types of household consumption are mostly subject to GST and which ones are mostly exempt.

This methodology has been developed to analyse the potential GST revenue impact resulting from changes in household consumption. It is of high importance due to its significant contribution to the State’s financial position and its ability to deliver positive outcomes to Victorians. In 2022‑23, GST revenue was Victoria’s largest revenue source, accounting for around a quarter of total state revenue.

Limited research has investigated the impact of household consumption patterns on GST revenue. The Commonwealth Parliamentary Budget Office (2020)1 examined the impact of household consumption on GST revenue over the period before the onset of the pandemic; however, the report did not disclose the specific methodology utilised.

This paper addresses this knowledge gap by introducing a methodology that more effectively uses price and volume information by GST status to identify drivers of observed trends. The paper also investigates household consumption trends both before and after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the resulting impact on GST revenue.

Over the first period it was found that the share of household consumption subject to GST has steadily declined. This has been driven by stronger growth in GST-free goods and services relative to those subject to GST; headlined by rent, education, and health.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted the consumption patterns of Australian households, and in turn affected GST revenue. Most notably household consumption subject to GST fell sharply, caused by significant declines in spending related to tourism, hospitality, and in-person recreational activities.

As border restrictions and public health measures began to ease, household consumption subject to GST bounced back. This was driven by a wave of discretionary spending on hotels and restaurants, clothing and footwear, recreation and culture. This caused the share of household consumption subject to GST to increase by the most significant amount since the introduction of the GST.

Recent trends show that Australian households have started to pull back on consumption subject to GST, largely driven by a cutback on discretionary spending amidst cost-of-living pressures. It is likely that this trend will continue while cost-of-living pressures persist. The longer-term trajectory of the share of household consumption subject to GST will depend on whether any structural changes in household consumption emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic.

Footnotes

[1] Commonwealth Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) report into ‘Structural Trends in GST, 2020.

2. Literature review

The goods and services tax (GST) was introduced in July 2000 as part of a reform package to modernise the indirect tax system, replacing the Commonwealth wholesale sales tax (WST).

As the WST was levied only on goods and not on services, it grew increasingly inefficient as the services sector grew to over two-thirds of the economy.1

The GST is a consumption tax applied to goods and services. A key feature of the new GST system was that it levied a uniform rate of 10 per cent. This decreased the tax system’s complexity and administrative burden. It also minimised the tax distortions that characterised the WST’s multi-tax rate structure, which was a contributing reason for its abolition.2

The GST is administered by the Australian Taxation Office on behalf of the Australian states and territories, and receipts are distributed based on the advice of the Commonwealth Grants Commission (CGC). It is distributed based on the principle of horizontal fiscal equalisation, which seeks to ensure jurisdictions can provide similar levels of infrastructure and services to their residents.2

Around 75 per cent of total revenue raised from the GST is collected from household consumption expenditure, while the remainder is raised mostly from private investment. Some household consumption items are exempt from the GST - broadly speaking, these include rent, health, education, fresh food and some financial services.3

A 2020 report published by the Commonwealth Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) showed that the share of total household consumption subject to GST has been steadily declining since the introduction of the GST.

The report also showed that the following mostly GST-free categories in rent, food, education, and health spending all experienced strong growth and were key contributors to the declining relative share.

Footnotes

[1] Treasurer of the Commonwealth of Australia, Tax Reform not a new tax a new tax system, The Howard Government's plan for a new tax system, August 1998.

[2] Australian Treasury, Tax discussion paper, March 2015.

[3] Department of Treasury and Finance (VIC) analysis of ABS data.

3. Data

The methodology uses two primary data sources from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

- Household final consumption expenditure (HFCE)1 data retrieved from the quarterly and annual national accounts2 releases.

- GST data by household consumption category derived from the product details input-output (I-O) tables3.

Multiple data sources are required for this methodology due to the limited availability of the I-O tables. At the time of the analysis, the most recent instance of the I-O tables was released in March 2023 for the reference period of 2020-21, highlighting the significant time lag between the release and reference date of the I-O tables. In addition, there are historical time gaps in the release of historical I-O tables, for example, I-O tables were published for the reference year of 2009-10 but not subsequently published again until 2012-13. Effectively, these allow the use of six (6) I-O tables for this study over the years for the years 2015-16 to 2020-214. To infer information about GST revenue raised through household final consumption expenditure outside of the six years above, information from the I-O tables must be combined with other more timely data. In this paper, the I-O tables are integrated with household final consumption expenditure (HFCE) data that is available quarterly and annually from the ABS. By doing this, we show that the methodology introduced here can estimate GST revenue raised through household consumption over a wider timeframe than 2015-16 to 2020-21.

These data sources are integrated using ‘percentage GST-able’ estimators—that is, the percentage of household consumption subject to GST for each of the 17 broad household consumption categories (e.g. health and education). These estimators are derived over the period from 2015-16 to 2020-21 by dividing total GST (derived from I-O tables) by total consumption (derived from annual national accounts) by category5. Note that GST revenue by household consumption category is derived using the Input Output Product Classification (IOPC) to HFCE concordance, as the I-O tables are cut by IOPC category.

Once derived, these estimators can be applied to timely quarterly national accounts data by multiplying them with total consumption in a given period. This allows one to use 2015-16 to 2020-21 information to infer the amount of GST revenue collected by household consumption category at any point in time before 2015-16 and after 2020-21, e.g. the March 2023 quarter.

Footnotes

[1] This analysis does not account for ‘net expenditure overseas’ in the household consumption data. Net overseas expenditure is a balancing item in the household consumption data that adjusts for expenditure overseas minus expenditure by non-residents in Australia. Historically, net overseas expenditure has been small as a share of total consumption. Between 2000-01 and 2022-23 it averaged at just 1.6 per cent of annual total HFCE.

[2] ABS Cat No. 5204.0 and 5206.0.

[3] ABS Cat No. 5215.0.55.001.

[4] For a detailed explanation of the ABS methodology applied to input-output tables, refer to: Australian National Accounts: Input-Output Tables methodology, 2020-21 financial year.

[5] Minimal variation was found across each of the six financial years for the ‘percentage GST-able’ estimators across each category, indicating minimal distortions arising from the COVID-19 pandemic.

4. Empirical approach

The empirical approach used for this research paper.

4.1 A methodology for estimating GST attributable to household consumption

Step 1: Aggregate GST by household consumption category

The first step in the methodology (see flow chart in Figure 1) involves aggregating GST expenditures by household consumption categories using I-O tables. The consumption data is categorised into 17 unique household consumption categories as defined by the ABS (see Table 1, Appendix B – Categorisation of household consumption categories). The aggregation is achieved by mapping each unique Input‑Output Product Classification (IOPC) category to its associated household consumption category and summing up the total GST derived from final household consumption expenditure. To estimate the consumption value of expenditure (i.e. before GST was charged) the resulting amounts are divided by 10 per cent1.

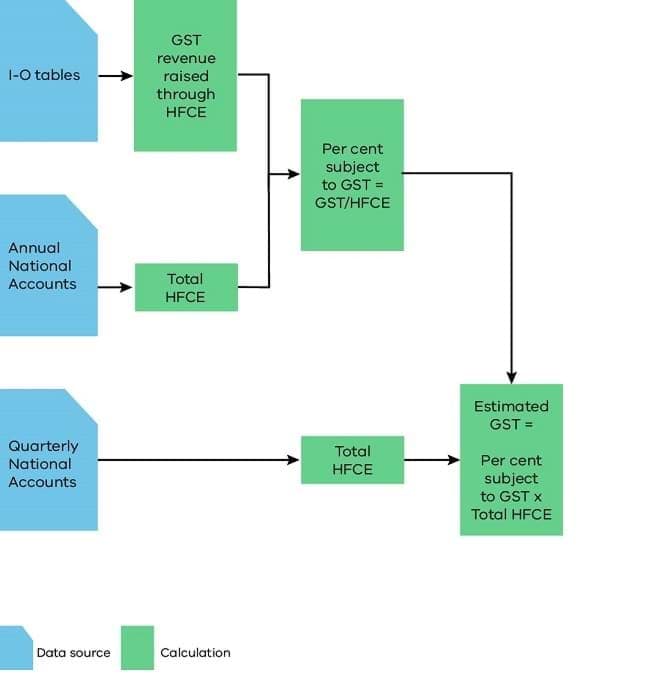

Step 2: Calculate ‘percentage GST‑able’ estimators

The consumption value of total subject to GST expenditure by household consumption category, derived in the previous step, is then divided by the total expenditure2 of the corresponding category in the same time period. This calculation can be repeated across multiple time periods3.

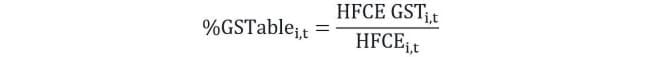

Where:

i represents the household final consumption expenditure (HFCE) category.

t represents the time period.

Step 3: Determine a representative ‘percentage GST‑able’ estimator

It is the responsibility of the analyst to review the estimated ‘percentage GST‑able’ estimators by category across the estimated time periods to determine an appropriate estimator for deriving the GST on household consumption time series.

Selecting a representative percentage GST‑able estimator could involve using a simple average if the estimator for a category is broadly similar across years, or a weighted average might be more appropriate to place more emphasis on specific years. Other methods or judgment can be applied to determine a representative estimator for each household consumption category.

Step 4: Derive the GST on household consumption time series

To derive the GST on household consumption series by category, the selected ‘percentage GST‑able’ indicators, determined in the previous step, are multiplied with quarterly household consumption data.4 The GST-free household consumption series can be estimated by subtracting the derived subject to GST series from total household consumption by category.

Figure 1 – Methodology flow chart for estimating GST revenue raised through household consumption

Note: HFCE refers to household final consumption expenditure.

4.2 What are the key concepts of household consumption subject to GST?

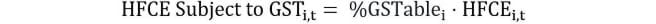

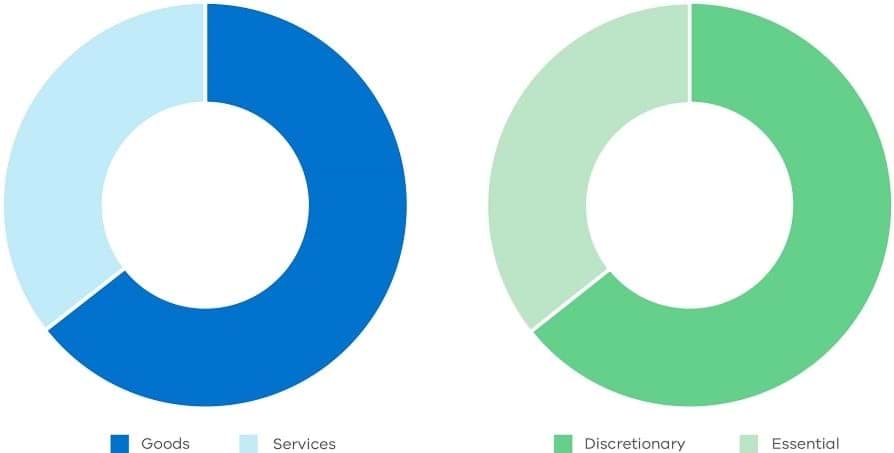

GST-able household consumption, by consumption type

The composition of household consumption subject to GST ('GST-able') is an important consideration for understanding how different types of household consumption influence changes in GST revenue. Goods consumption and discretionary5 spending make up a significant share of GST derived from household consumption. See Figure 2.

Figure 2: Annual share of total ‘GST-able’ household consumption by goods vs services consumption

Source: DTF analysis of ABS data.

Percentage ‘GST-able’ and ‘share’ of household consumption, by consumption category

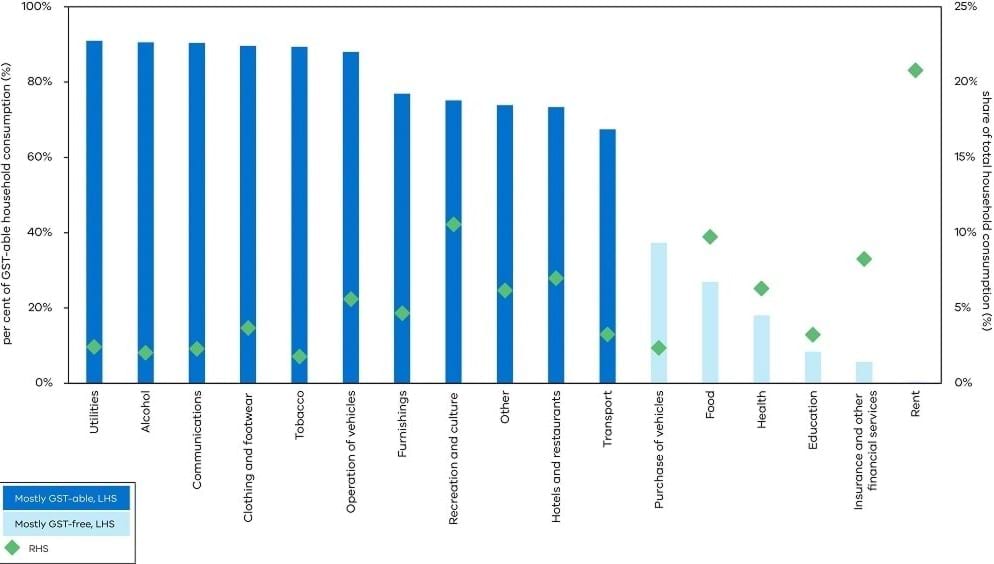

The composition of household consumption subject to GST ('GST-able') is an important consideration for understanding how different types of household consumption influence changes in GST revenue. GST-able estimators reveal that only a small number of household consumption categories are considered mostly GST-free. Goods consumption and discretionary spending make up a significant share of GST derived from household consumption. However, we also find that despite representing a small number of categories, the mostly GST-free items represent a significant share of total consumption by Australian households.

The six categories considered mostly GST-free represent around 50 per cent of the share of total household consumption,6 headlined by rent which accounts for around a fifth of total household consumption. This reveals that the size of the consumption category (or relative share of total household consumption) is an important consideration when analysing the impact of growth between consumption categories (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Percentage ‘GST-able’ and ‘share’ of total household consumption, by household consumption category

Source: DTF analysis of ABS data.

Footnotes

[1] The current rate of GST is 10 per cent.

[2] ABS Cat No. 5204.0.

[3] Analysis in this report uses data from I-O tables over the period of 2015-16 to 2020-21.

[4] ABS Cat No. 5206.0.

[5] Refer to the list of household consumption categories, categorised by goods versus services and discretionary versus essential, in Appendix B.

[6] This figure represents the total consumption of each category. For example, it is assumed that 100 per cent of food consumption is GST-able, when in fact it is estimated that about a quarter of food consumption is GST-able.

5. Results

In this section, we discuss our results from the application of the methodology to estimate GST revenue using household consumption data from July 2000 to December 2023.

We describe our results from analysing household consumption as a whole and by GST status. We also discuss consumption trends across the broad commodity categories.

5.1 Since the introduction of the GST

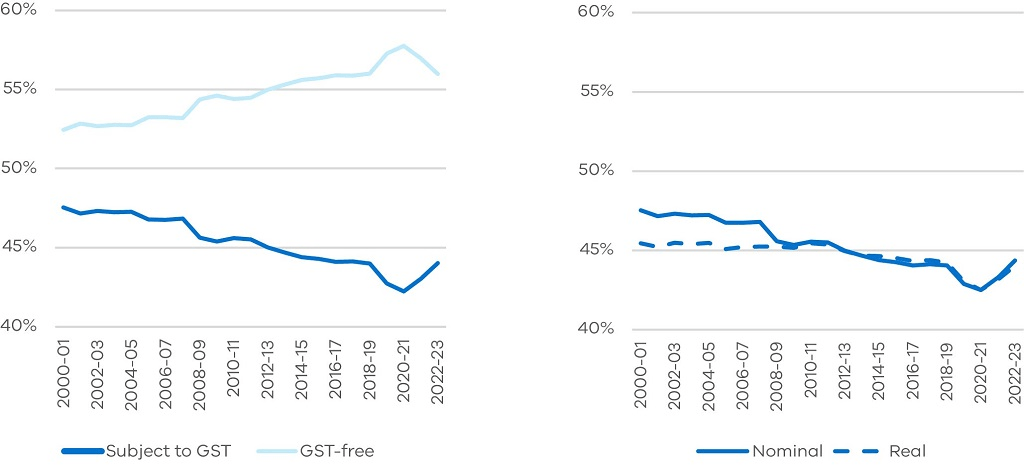

Figure 4 depicts the trends of GST-able and GST-free consumption over time. It can be seen that since July 2000, there has been a steady decline in the share of household consumption that was subject to GST ('GST-able'). At the same time, the relative share of GST free household consumption has increased over time. In the first decade (2000-2009), analysis reveals that the share of nominal household consumption subject to GST declined while real household consumption subject to GST remained flat. This observation suggests that the key driver of the decline in nominal terms was relatively stronger growth in the prices of goods and services that are GST-free. In the next decade, Australian households appears to have begun purchasing a greater share of GST-free goods and services (in real terms), contributing to the decline in the share of GST-able household consumption.

One possible explanation for this observed trend is movement in the exchange rate. As is known, the price of imports plays an important role in GST collections, with GST collected on imports accounting for around 50 per cent of total GST.1 In this case, during the early years of the GST, a rising Australian dollar caused import prices to fall, causing the relative share in the price of goods and services subject to GST to decline. This contributed to a decline in the share of nominal household consumption subject to GST over the first decade of the century, while the share in real household consumption of goods and services remained flat.

Meanwhile, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia in March 2020 brought about significant changes in household consumption patterns. It is clear from the diagram that the share of GST-able household consumption followed a U-shaped (or V-shaped) trajectory, indicating that the pandemic had a two-part effect on consumption patterns: one which saw an acceleration of the pre-pandemic trend, followed by a divergence from the pre‑pandemic trend (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Annual share of total household consumption by GST status (%)

Note: Excludes GST from private gross fixed capital formation (private investment), which is around 25 per cent of total GST.

Source: DTF analysis of ABS data.

5.2 Before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic

The share of GST-able household consumption declined steadily over the pre-pandemic period. This was driven by a combination of relatively lower price2 and real consumption growth for GST-able items at different stages of the two decades leading up to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Over this period, household consumption that is GST-free grew by around 34 percentage points more than spending on GST-able goods and services (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Percentage change in household consumption since the introduction of the GST to December 2019 by GST status

Source: DTF analysis of ABS data.

High pre-pandemic growth at the category level was headlined by mostly GST-free categories in education, health, and rent - all among the five fastest growing categories. Utilities, transport, and alcohol consumption were amongst the strongest growing mostly GST-able items. However, these categories represent a smaller share of household consumption, particularly utilities and alcohol consumption, which represent 2.4 and 2.0 per cent of total household consumption, respectively. The categories experiencing the lowest growth rates mainly comprised of mostly GST-able items, which experienced low price growth (some negative) (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Household consumption expenditure, average annual growth (%), 2000-01 to 2018-19

Source: DTF analysis of ABS data, inspired by the PBO report into structural trends in GST (2020).

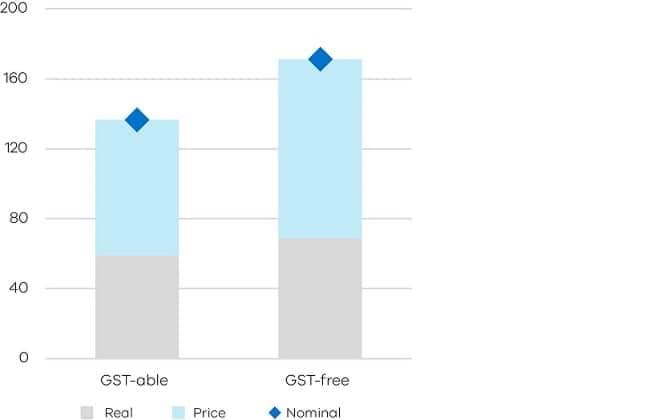

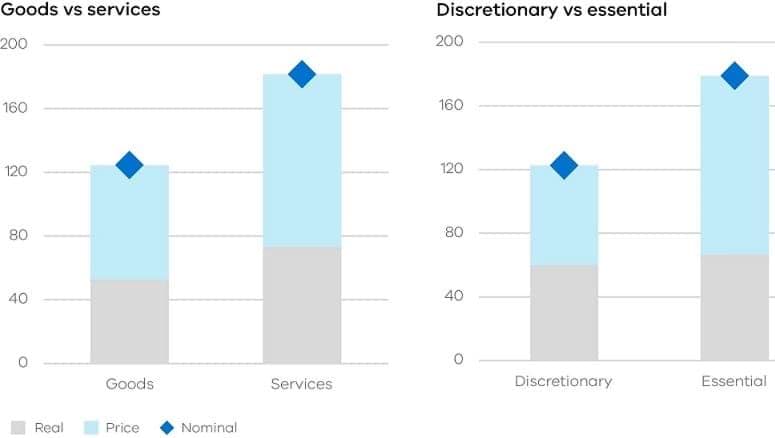

Over the two decades leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, spending on services and essential items significantly outpaced the growth in the consumption of goods and discretionary items. Services consumption outpaced 'goods' consumption by almost 50 percentage points, driven primarily by relatively stronger price growth. A similar pattern was observed with essential consumption outpacing discretionary spending (see Figure 7).

This supports the steady decline in the share of GST-able household consumption over this period, as it primarily consists of goods and discretionary spending, which experienced slower growth.

Figure 7: Percentage change (%) in household consumption since the introduction of the GST to Dec 2019, goods vs services

Source: DTF analysis of ABS data.

5.3 Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic

In terms of the consumption patterns of Australian households, the COVID-19 pandemic period can be broken down into two phases: the first was characterised by necessary public health restrictions leading up to the September quarter 2021, then the second, the post-lockdown phase where these restrictions were eased.

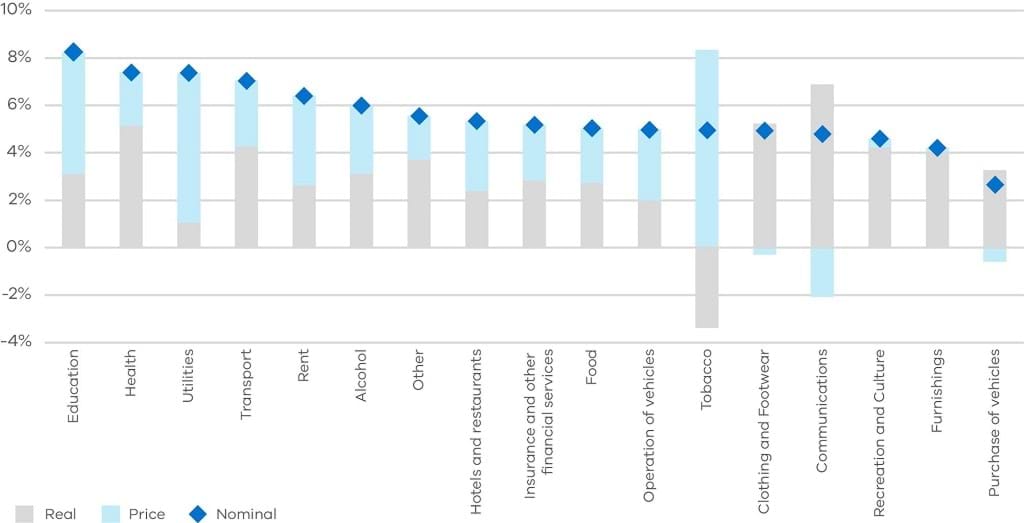

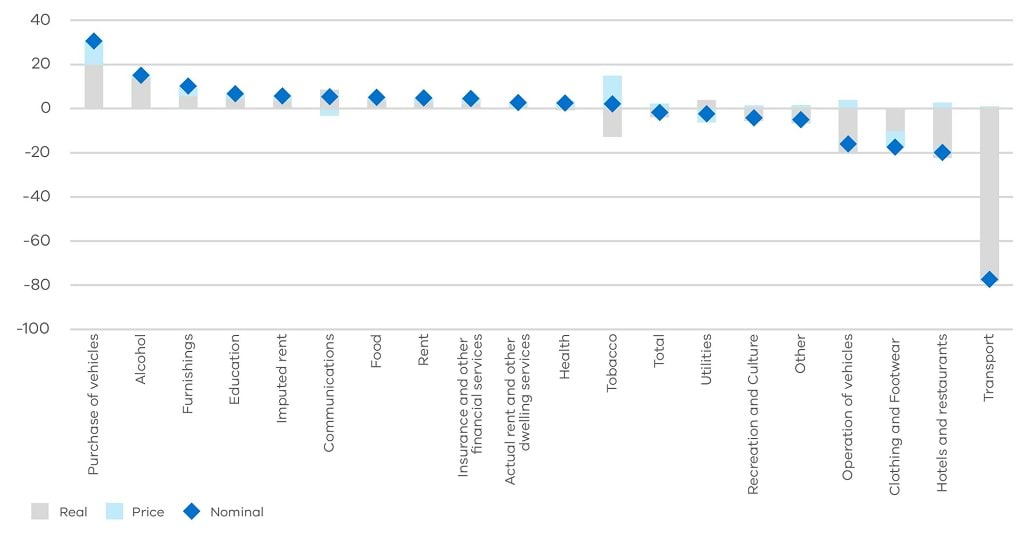

Necessary public health measures enforced in Australia resulted in a significant reduction in travel and tourism-related consumption, as evidenced by large falls in the real consumption of 'hotels and restaurants' and 'transport' (which includes air travel). In-person activities were also limited or restricted, leading to declines in the real consumption of recreational and cultural activities. On the flip side, with households being limited in the consumption of some items, other categories experienced high rates of growth, including the purchase of vehicles (which exhibited the weakest growth pre‑pandemic), alcohol and home improvement consumption (as measured by the furnishing category) (see Figure 8).

The overall impact of these consumption patterns resulted in a sharp decline in the share of GST-able household consumption in the lead-up to the September quarter 2021.

Figure 8: Percentage change since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic to the September quarter 2021

Source: DTF analysis of ABS data.

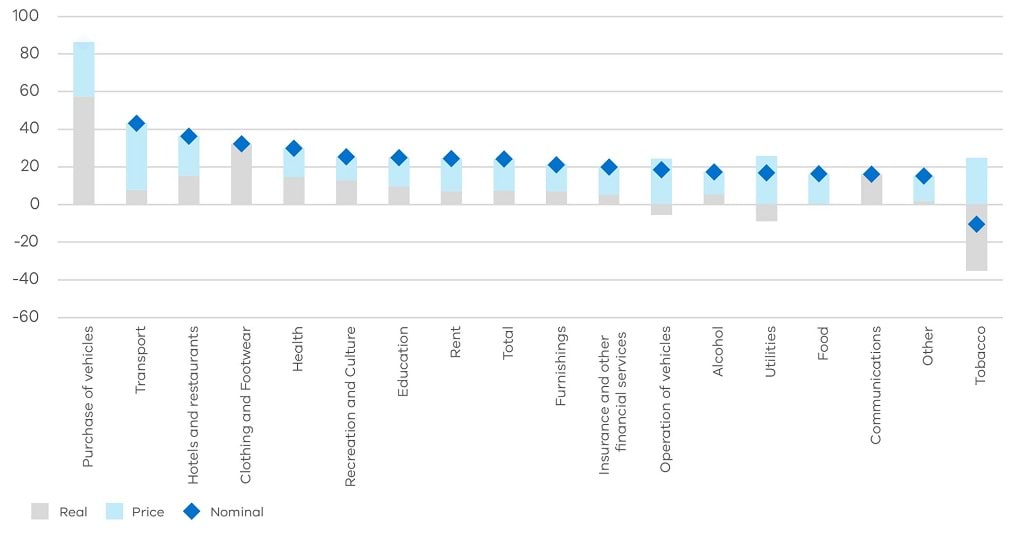

As restrictions began to ease across Australia, household consumption patterns shifted, resulting in a sharp increase in the share of GST-able household consumption. This increase represented the most significant rise since the GST was introduced. The increase was largely driven by a wave of spending on previously restricted consumption categories such as hotels and restaurants, transport, and recreation and culture, all of which have grown by more than 25 per cent compared to pre-pandemic levels. Growth in mostly GST-free items such as health, rent, and education has been strong but relatively subdued compared to the GST‑able items previously mentioned.

Some other trends in household consumption show that rising inflation has caused broad-based price growth across most categories. For example, food consumption3 has grown by around 15 per cent relative to the pre-pandemic period and is almost entirely driven by rising prices. Additionally, the purchase of vehicles has been an emerging consumption pattern of the COVID-19 pandemic period (which exhibited the weakest growth pre-pandemic), growing strongly in both phases of the COVID-19 pandemic period. At present, the purchase of vehicles is almost double pre-pandemic levels, driven by an increase of around 60 per cent in real consumption and 30 per cent in prices (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Percentage change since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic to the December 2023 quarter

Source: DTF analysis of ABS data.

Relative to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and up until the December quarter of 2023, growth in GST-able and GST-free household consumption has been broadly the same. However, their trajectories over the course of the COVID-19 pandemic are different. GST-able household consumption was more adversely affected by COVID-19 public health measures, as evidenced by deeper troughs compared to GST-free consumption.

This can be explained by the composition of items in each category. GST-free items include the consumption of food, health, rent, education, financial services, and the purchase of vehicles. It is clear that these consumption items were less affected by necessary public health restrictions compared to the GST-able categories such as transport and hotels and restaurants.

Interestingly, recent household consumption patterns show signs that spending on GST-able goods and services has begun to slow, as reflected by a slowdown in real terms household consumption subject to GST (see Figure 10). This would suggest a reversion towards the pre-pandemic trend of a declining share of GST-able household consumption (see Figure 4).

Figure 10: Household consumption growth since the COVID-19 pandemic, by GST-able and GST-free, index March 2020 = 100

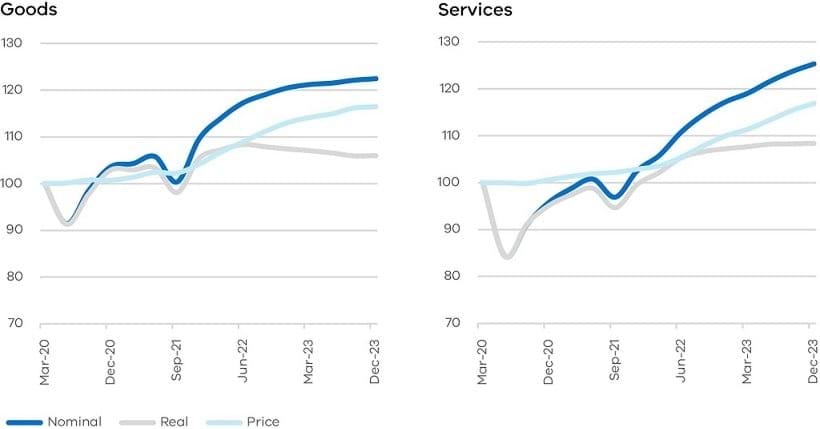

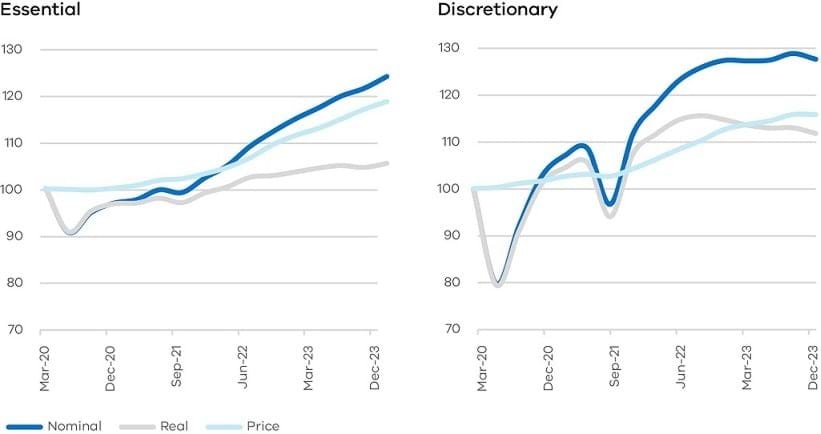

Growth in consumption of ‘goods’ and ‘services’ relative to pre-pandemic has has grown at almost equal rates to the December quarter 2023. Over the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, services household consumption experienced a larger decline than spending on goods, largely due to the enforced border restrictions which limited the consumption of tourism related services.

As necessary public health restrictions eased over the second phase since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, strong price growth contributed to increases in the consumption of both goods and services. In recent quarters, there are signs that Australian households are moderating their overall consumption (in real terms) in response to a challenging economic environment. Most notably, the real consumption of goods has begun to decline, contributing to a slow down in the real household consumption of GST-able items (see Figure 11).

Figure 11: Household consumption growth since the COVID-19 pandemic, goods, index March 2020 = 100

Source: DTF analysis of ABS data.

Growth in spending on discretionary items relative to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and up until the December quarter 2023 remains elevated compared to essential consumption. Strong expenditure on discretionary household consumption has been a key reason for the share of GST-able household consumption rise over the two years since COVID-19 pandemic restrictions eased.

However, data in recent quarters suggest that Australian households may have started to pull back on discretionary expenditure, which would place downward pressure on the share of GST-able household consumption (see Figure 12).

Figure 12: Household consumption growth since the COVID-19 pandemic, essential, index March 2020 = 100

Source: DTF analysis of ABS data.

Footnotes

[16] Parliamentary Budget Office (2020) report into Structural Trends in GST.

[17] Prices are an approximation and do not represent actual CPI.

[18] Refers to food purchased by households mainly for consumption or preparation at home.

6. Conclusion

This paper has introduced a data-driven methodology for estimating GST revenue raised through household consumption, enabling the monitoring of trends in household consumption patterns and their impact on GST revenue.

Understanding and monitoring the underlying changes in GST revenue is of significant importance to jurisdictions such as Victoria, which receive a significant proportion of state revenue through GST grants. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruptions to household consumption, which contributed to volatile movements in GST revenue. This paper has applied the new methodology and analysed trends in GST revenue over two distinct periods – before and after the onset of the pandemic.

Over the period since the introduction of the GST in July 2000 and before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020, the share of household consumption subject to GST has declined steadily. This was found to be driven largely by strong growth in expenditure on essential items, compared to discretionary spending, and on services, compared to goods. Both essential items and services are largely considered exempt from GST, thereby contributing to the declining share of household consumption subject to GST.

The individual consumption categories supporting this trend were headlined by strong growth (relative to other consumption categories over this period) in rent, education, and health. Some consumption categories that are mostly subject to GST, such as utilities and alcohol, experienced strong growth before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, their impact on the share of household consumption subject to GST was insignificant given their relatively small share of total household consumption.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic caused significant changes to household consumption, most notably in travel, tourism and recreational in-person activities. This led to significant declines in discretionary and services-based consumption during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic when necessary public health restrictions were enforced across the country. These changing consumption patterns caused a sharp fall in the share of household consumption subject to GST.

As border restrictions and public health measures began to ease, a wave of discretionary spending followed, supported by large savings buffers accumulated during the COVID-19 pandemic. This is reflected in above trend growth in spending on hotels and restaurants, clothing and footwear, recreation and culture (25 per cent). This ultimately led to an increase in the share of household consumption subject to GST for one of the few times since the introduction of the GST.

Despite gains in the share of household consumption subject to GST, this share is beginning to wane as cost-of-living pressures on households intensify. Real household consumption subject to GST has declined over the last four quarters to December 2023. This has been driven by a pullback in goods and discretionary-based consumption, which are predominately subject to GST.

The share of household consumption subject to GST is expected to continue slowing in the near term as households moderate spending on discretionary items amidst cost-of-living pressures. The longer-term outlook for GST revenue raised through household consumption is more uncertain. It will depend on whether some of the structural changes in consumption patterns that emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic persist, such as reduced travel expenditure due to some workers working fewer office days.

Appendix A

Appendix A: Value, price, and volume.

Current prices – ‘value’ or ‘nominal’

Current prices are measured by a combination of quantity and unit prices. Each household consumption category is likely to have multiple sub-categories with different quantities and unit prices that vary over time.1

For example, consider the consumption category food, of which rice and pasta are two different sub‑categories. The current value of ‘rice’ in period t is measured by the quantity multiplied by the unit price in period t. Pasta is measured in the same process but may have a different quantity and price. The general formula used to value current prices is:

Where:

CPt is the current price value at time t

qt is the quantity at time t

pt is the unit price at time t

The current price value of ‘food’ can be measured as follows:

The valuation of ‘current prices’ involves considering both quantity (volumes) and unit prices (prices), making it a metric for assessing the overall household consumption within each category.

Chain-volume – ‘volumes’ or ‘real’

Chain-volume measures provide an alternative measurement for quantifying volumes compared to constant price estimates. Unlike constant price estimates, which evaluate changes in quantity relative to a fixed base period updated every five years, chain-volume measures are updated annually using prices from a designated base period. These annual reweighting volume change measures are then systematically linked together to construct a time series of chain volume measures.

Chain-volume measures isolates the effect of quantity (or ‘volumes’) and therefore can be used to analyse volumes.

Prices

The price series is obtained by subtracting ‘values’ (or current prices) from ‘volumes’ (or chain‑volumes). It's important to note that series in levels cannot be directly subtracted to determine prices. However, utilising percentage series, such as average annual change, allows for an approximation of prices.

Footnotes

[19] ABS, Demystifying Chain Volume Measures.

Appendix B

Appendix B – Categorisation of household consumption categories.

Table 1 - Classification of household consumption categories

| Household consumption categories | Goods/services | Essential/discretionary |

| Electricity, gas and other fuel | Goods | Essential |

| Alcoholic beverages | Goods | Discretionary |

| Communications | Services | Essential |

| Clothing and footwear | Goods | Discretionary |

| Cigarettes and tobacco | Goods | Discretionary |

| Operation of vehicles | Goods1 | Essential |

| Furnishings and household equipment | Goods | Discretionary |

| Recreation and culture | Goods2 | Discretionary |

| Other goods and services | Services3 | Discretionary |

| Hotels, cafes and restaurants | Services | Discretionary |

| Transport services | Services | Essential4 |

| Purchase of vehicles | Goods | Discretionary |

| Food | Goods | Essential |

| Health | Services5 | Essential |

| Education services | Services | Essential |

| Insurance and other financial services | Services | Essential |

| Rent and other dwelling services | Services | Essential |

Note: Determined using ABS classifications.

Footnotes

[20] Most sub-categories of the operation of vehicles category are considered goods.

[21] Most sub-categories of the recreation and culture category are considered goods.

[22] Most sub-categories of the other goods and services category are considered goods.

[23] Most sub-categories of the transport services category are considered essential.

[24] Most sub-categories of the health category are considered services.