This study draws on the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey to examine the role of higher education on employment outcomes in the graduate employment market. The HILDA Survey tracks approximately 17 000 individuals in some 9 500 Australian households annually through time, beginning from 2001 when the survey was first conducted. We use HILDA survey waves from 2001 thru to 2018 to draw the sample of households used for this study.

This paper restricts analysis to those individuals who have obtained or completed a tertiary degree during the HILDA survey years. This group would include all those who completed a bachelor’s degree, an honour’s degree, a graduate diploma or certificate, a master’s degree or a PhD. Available data at the individual level include age, gender, marital status, health, ethnicity, education and employment. Available information on individuals’ jobs have also been used, including details on occupation type, industry type, broad conditions of contract as well as periods of unemployment or voluntary absence from the labour market and why. The total number of persons in the pooled sample is 14 192, which is equivalent to approximately 2030 unique individuals who appeared in the survey for a given period. The number of years that individuals are observed in the sample ranges from one year to 17 years, with a median of 6.5. This set of individuals will comprise the paper’s analytical sample, hereon simply referred to as the sample.

The distribution of the sample between genders across variables of interest are tabulated in Table 1. Across all people, the sample consists of 40 per cent men and 60 per cent women with ages ranging from 17 to 59 years.1 Seventy per cent of all people are aged 25 to 44 and close to 80 per cent live in major cities. All have completed at least a bachelor’s degree and close to a half have completed a postgraduate qualification as well. Further, 89.6 per cent of people in the sample are employed, 2.5 per cent are unemployed and the remaining 7.9 are classified as Not In Labour Force (NILF).2 This latter group consists of those who are not actively looking for work in the specified period, for various reasons, and includes a subset of people who are referred to as ‘discouraged job seekers’.

Table 1. Description of variables

| Variable | Male | Female | All | |

| Gender | 40.7 | 59.4 | N=14192 | |

| Age group | < 25 | 14.8 | 16.9 | 16.0 |

| 25-44 | 71.7 | 67.5 | 69.2 | |

| 45-64 | 13.5 | 15.7 | 14.8 | |

| Location | Urban | 18.9 | 23.1 | 21.4 |

| Rural | 81.1 | 76.9 | 78.6 | |

| Education (% row) | ||||

| - PhD/Masters | 41.7 | 58.3 | 100.0 | |

| - Grad Dip/Cert | 39.9 | 60.1 | 100.0 | |

| - Bachelors/Honours | 40.5 | 59.5 | 100.0 | |

| Education (% column) | ||||

| - PhD/Masters | 26.1 | 25.0 | 25.4 | |

| - Grad Dip/Cert | 22.2 | 22.9 | 22.6 | |

| - Bachelors/Honours | 51.7 | 52.1 | 51.9 | |

| LF Status (% row) | ||||

| - Employed | 42.4 | 57.6 | 100.0 | |

| - Unemployed | 43.2 | 56.8 | 100.0 | |

| - NILF | 19.7 | 80.3 | 100.0 | |

| LF Status (% column) | ||||

| - Employed | 93.5 | 86.9 | 89.6 | |

| - Unemployed | 2.7 | 2.4 | 2.5 | |

| - NILF | 3.8 | 10.7 | 7.9 | |

| LF status (employed only, % row) | ||||

| - Full-time | 46.0 | 54.0 | 100.0 | |

| - Part-time | 29.19 | 70.81 | 100 | |

| LF Status (employed only, % column) | ||||

| - Full-time | 77.1 | 62.1 | 68.2 | |

| - Part-time | 22.75 | 37.82 | 31.7 | |

| Job contract (among those employed; % row) | ||||

| - Fixed term | 34.32 | 65.68 | 100 | |

| - Casual | 36.38 | 63.62 | 100 | |

| - Permanent | 44.6 | 55.4 | 100 | |

| - Other | 30.77 | 69.23 | 100 | |

| Job contract (among those employed; % column) | ||||

| - Fixed term | 14.38 | 19.77 | 17.51 | |

| - Casual | 10.2 | 12.82 | 11.72 | |

| - Permanent | 75.25 | 67.15 | 70.54 | |

| - Other | 0.16 | 0.26 | 0.22 | |

| Industry | ||||

| - Construction | 80.74 | 19.26 | 100 | |

| - Mining | 67.55 | 32.45 | 100 | |

| - Transport, postal and warehousing | 72.78 | 27.22 | 100 | |

| - Education and training | 29.17 | 70.83 | 100 | |

| - Health care and social assistance | 22.3 | 77.7 | 100 |

Details in the labour force status of the sample present further distinctions along gender lines. Among all who are employed, seven in every 10 work full time, while the rest work in a part-time capacity. Seventy-seven per cent of men surveyed are in full-time jobs compared to 62 per cent of the women. Eight in every 10 people working part-time are women, who mostly cite childcare as the main reason for working part-time. In contrast, among part-time workers who are men, only 5 per cent cited childcare as the main reason for being in part-time work, while over 40 per cent of men in part-time positions cited other non-care personal or family obligations as their main reason.

In terms of job contract types, over 70 per cent of those employed are in permanent positions, 18 per cent are on fixed-term contracts and about 12 per cent work as casuals. The women in the sample were significantly more likely to be employed in fixed-term and casual positions. Correspondingly, the proportion of men in permanent employment is significantly higher than that of women. Lastly, there is some evidence of occupational segregation in the sample, with men heavily concentrated in the construction, mining and transport industries, and women heavily concentrated in education/training and health care industries. This is not at all surprising, except when noting that the education and health care industries comprise 39 per cent of the total workforce in the sample while the top three male-dominated industries comprise less than 6 per cent of the total workforce.

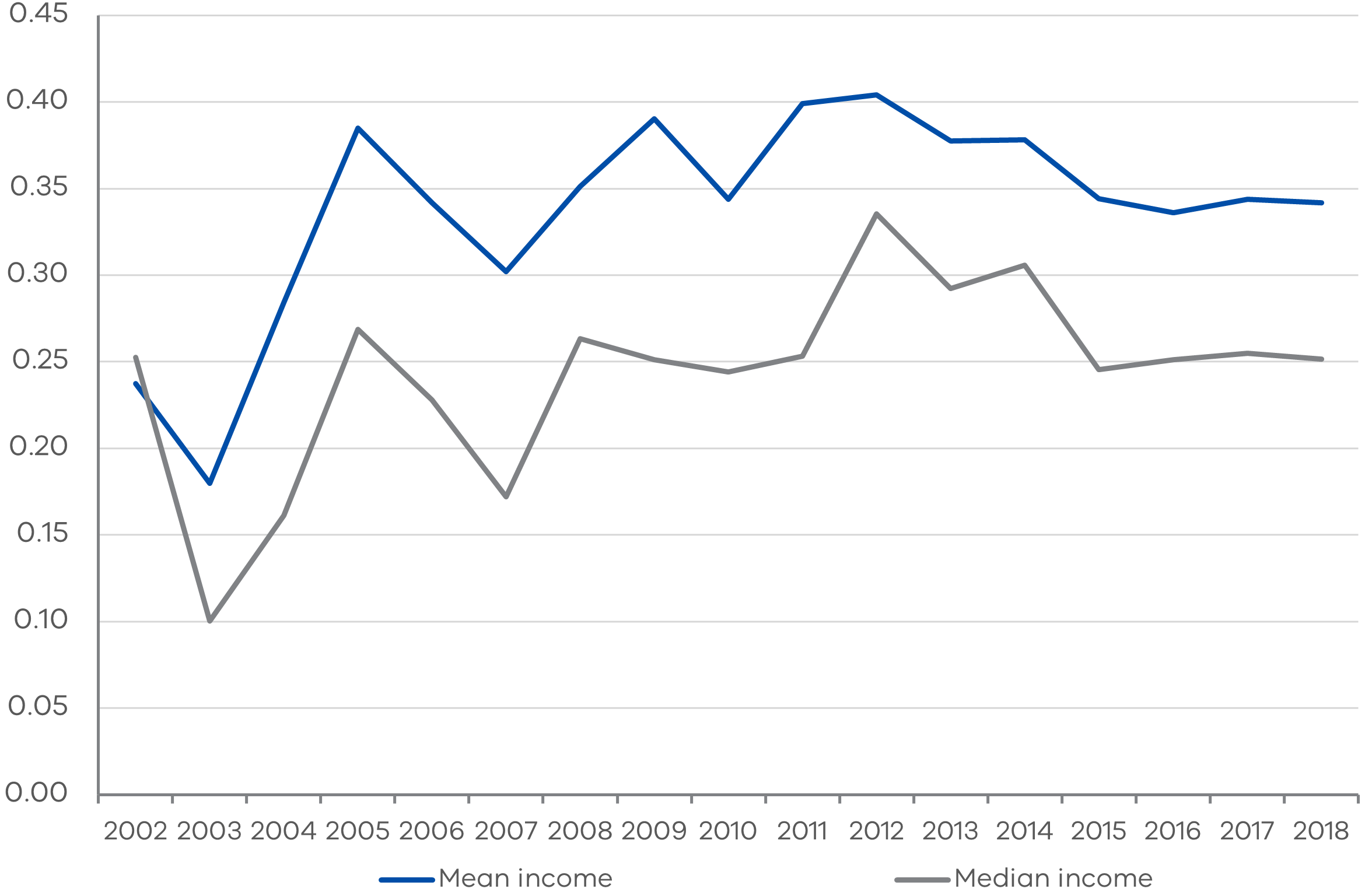

Figure 1: Gender pay gaps, mean and median incomes

Source: Author’s calculation from HILDA sample.

Large disparities in pay between men and women are also evident in the sample. For a formal measure, we analyse trends in the gender pay gap, GPG, defined as:

where Ym and Yf denote male and female incomes, respectively. We calculate GPG using mean and median incomes and graph the points over time in Figure 1. In terms of mean incomes, the income gap between men and women in this sample is about 35 per cent. The pay gap grew by about 5 per cent each year between 2002 and 2012, when it peaked at 40 per cent. The gap has declined since and stood at 34 per cent in 2018. The median income GPG curve is seen to rise and fall in similar magnitudes as the mean income GPG curve, although the median wage curve sat consistently lower than the mean wage curve by about 10 percentage points all through the study period. It is interesting to note that the pay gap between men and women in Australia rapidly rose during the mining boom years of 2002 and 2012 and appears to have settled to a new high in the years after that. The wage gap did not seem to be affected by the economic shocks experienced due to the global financial crisis (2007–2008). Similar trends can be seen in the wage gap calculated using median incomes.

Table 2. Quintile distribution using SEIFA Index

| Male | Female | All | ||||

| Quintile | No | % Share | No | % Share | No | % Share |

| Quintile 1 (lowest) | 421 | 8.5 | 723 | 9.8 | 1144 | 9.3 |

| Quintile 2 | 576 | 11.7 | 1017 | 13.8 | 1593 | 13.0 |

| Quintile 3 | 695 | 14.1 | 1295 | 17.6 | 1990 | 16.2 |

| Quintile 4 | 1259 | 25.5 | 1809 | 24.6 | 3068 | 25.0 |

| Quintile 5 | 1981 | 40.2 | 2508 | 34.1 | 4489 | 36.5 |

The distribution of the sample across the income quintile is shown in Table 2. Given that this cohort of individuals are all tertiary-educated, the distribution is highly skewed towards the left. The top 20 per cent account for over 36 per cent of total income, while the poorest 20 per cent account for less than 20 per cent of the total income pool. A higher share of men in the top two quintiles is also evident and a higher share of women relative to men is observed in the lowest and middle-income quintiles.

Footnotes

[1] All persons are aged 25 to 59 in CY2018, but 17 is the youngest age a person is observed in the sample.

[2] Using definitions by the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Updated